In recent months, the Port of Portland’s probable loss of the Hanjin shipping company has been in the news. Local media reported on the event, largely painting it as a minor tragedy. Chris, here at Portland Transport, provided his own take, noting how that those businesses using Terminal 6 would now have to truck their goods to Puget Sound, an increase not only in cost but also in carbon emissions.

I have a slightly different take from Chris: container traffic at the Port of Portland is doomed. It is only a question of when.

Hanjin’s departure has sparked a lot of silly analysis. An Oregonian editorial, for example, blamed most of the matter on increased costs from labor disputes, an issue that the Port of Portland claims was a factor in Hanjin’s decision. (The official press release does not mention this factor, nor does the Hanjin letter to shipping customers [PDF] obtained by the Oregonian.)

Meanwhile, the Portland Business Journal sloppily threw a bunch of statistics at the matter, attempting to make the case that Hanjin in specific, and container import-export at the Port of Portland in general, were crucial to the metropolitan economy.

Hanjin’s decision comes as the region executes on a plan to increase exports, which are a significant contributor to the Portland metro economy. A recent Brookings Institution study found that exports accounted for $33.9 billion in regional economic activity in 2012, driving in large part by technology exports. (See the region’s top-five exported goods.)

In addition, a recent Portland Business Alliance study found that Oregon companies made and exported $16.5 billion worth of goods to countries worldwide in 2012, creating 490,000 jobs.

Not all of those good were moved by Hanjin, but as the largest carrier calling on Portland, Hanjin certainly accounted for a good deal of that traffic.

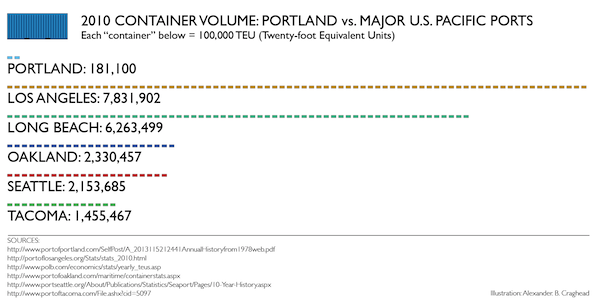

Reading this take from the Portland Business Journal, one might conclude that Hanjin was doing massive amounts of business out of T6, and the the Port of Portland was some kind of big time player in container shipping. Yet this is not at all the case. Terminal volume at T6 for the year 2012 (the most recent year for which data was available) stands at 183,203 TEU. (TEU means “twenty-foot equivalent units,” representing a standard twenty-foot shipping container.) Moreover, T6 has never handled more than 340,000 TEU in a year, and that was ten years ago, in 2003. While this may seem like a lot, let’s put it into perspective, by comparing the Port of Portland’s container traffic to the other major west coast terminals at Los Angeles, Long Beach, Seattle, Oakland, and Tacoma. The following graphic, based on 2010 volumes, gives you some sense of proportion:

Portland is the smallest “major” U.S. container port. Tacoma, the next larger, is more than eight times bigger. As a player in the global container shipping market, Portland doesn’t even exist.

To understand why we need to understand the special nature of containerized cargo. This is the type of stuff that is not so time sensitive or small that it can economically fly, but is of sufficient value and lightness that it can be shipped relatively cheaply and still be competitively sold at its destination. Inbound containerized cargo to the United States is often consumer goods manufactured in Asia. Outbound cargo is typically specialty products or niche materials. In Oregon, examples might be specialty cedar boards for Japanese sauna construction, pallets of Christmas trees headed to Hawaii, or a couple truckloads of Hazelnuts going to China.

Containerized cargo, because it is relatively light and of higher value, is very mobile. Outbound loads will go to the port where shipping companies can offer the fastest transit time to the final destination for the least cost, and that recipe usually means that containers end up shipping in and out where other containers already are, since competition breeds lower costs. It also means that containers tend to go to those ports that are closest to their final destinations, thus reducing transit times. This is why goods heading to Europe typically are trucked or carried by railways to Eastern ports, while goods heading to Asia typically go west to Pacific ports.

So far, you’d think, so good for Portland. Since we are a Pacific port, we’re closer to Asia. But so are all the other ports of the U.S. West Coast. This is were port competitiveness begins. Note that when Hanjin announced its pull out from Portland, the Puget Sound Business Journal treated it as good news: container traffic lost in Portland would likely relocate to Puget Sound ports. In the American shipping world, what is bad for one port is good for all the others.

To compete, each port has its unique characteristics. Portland, along with there ports of the lower Columbia River, has a geographic advantage by being at the mouth of the Columbia River Gorge, the only water-level route through the Cascade-Sierra divide. This makes these ports naturally strong for handling bulk materials, where mobility is heavily restricted by weight and a high shipping cost. According to statistics published by the Port of Portland, Portland Harbor — which includes both the Port of Portland and several private terminals along the Willamette River — is “the largest wheat export port in the United States, the largest mineral export port on the U.S. West Coast, and the 4th largest export tonnage port on the U.S. West Coast.”

Container traffic is, however, highly mobile. Portland is located 100 miles away from the ocean, up a river with a relatively shallow depth (43 feet) and that must be dredged, and on the other side of one of the most treacherous river bars in the world. Put another way, to serve Portland, you have to have a reason to spend the extra time, money, and risk to reach it. All that grain can’t easily or cheaply move elsewhere, but containers — especially if they trucking in anyway and are not being filled directly from Portland producers — can fairly easily and cheaply end up at other ports.

And over the last half-century, that’s exactly what has happened. Railroads, truckers, and shipping lines have all contributed to the development of major container traffic at every major port of the U.S. Pacific Coast–except for Portland. No labor agreement or policy change is going to alter this historic trend.

14 responses to “The inevitable end of container traffic at the Port of Portland”

Interesting article, much appreciated. As a former recreational sailor, I have wondered about the depth and sandbar issues. In 2003, what were the volumes of the other ports? Were they higher as well, or has Portland lost even more market share than the raw numbers would indicate?

Are there any non-port cities that we can compare ourselves to? Do they have much manufacturing as part of their economic mix? If we were to “lose” the port, where would that really put us with regards to job loss, etc? If there are comparable places that don’t have sea ports but are doing just fine with regards to manufacturing jobs, then perhaps we don’t need to worry about ours. (It would typical Portland hipster ironicism to have a city named “Portland” without a port.)

Dwaine, it’s not so much that we will lose the port as we will, eventually, lose container traffic. The port is actually an impressive player in world grain shipments and also in automobiles. The former comes from natural advantages, the latter from careful building of a business to critical mass levels that other ports did not pursue as strongly.

The closest possible analogy might be Sacramento, which can be served by ocean-going vessels but largely is not, however, Sacramento did not have Portland’s great geograhy for grain movement.

We have great rail and highway connections here. I don’t think this will have much impact beyond the port jobs themselves.

Spot on! T-6 has been over hyped for years by the Port and others. Its biggest container export has been “air” ie empty containers. It by and large has nothing to do with the regional economy, and though it may hurt frozen potato chip producers in Idaho and ranchers who export straw cubes to Japan, etc.

Portland is a significant port, but not much of container port as was clearly pointed out.

What drives modern economies is not ports (auto imports?) or highways but major research universities. Oh for the business elite here to own up to this fact and get over the CRC and put a couple billion into education.

Lenny, I think I would argue ports do have major impacts on local and regional economies. I think it is less that the port has no impact as that ports are part of global transportation and logistics chains, and trying to fight those forces is like an ant trying to push a stone up a hill.

A.C.: Would you predict that the demise of container traffic may vacate space in Port of Portland that would be a prime candidate for coal exports?

Do the major trends you identify in this article effectively doom, at least for a decade or two, most efforts to develop more business at the Port of Coos Bay?

Considering the historic pattern of coal exports being sensitive to commodity price fluctuations, coal export terminals have been a risky thing to build on the West Coast. Note that Terminal 4’s potash facility was originally planned for coal, but when Australian coal drove world coal prices lower, American coal was no longer competitive and the terminal was switched over to other commodities.

Developments at Coos Bay are beyond the scope of Portland Transport. I will only say that they have their own unique combination of geography, infrastructure, and economy. But if you are asking if they are likely to see meaningful container traffic, I would say that the answer there is also no.

Coos Bay suffers from the problem of poor land connections (among other things). It’s connected to the interior by various two-lane highways, and by a railroad line that is prone to flood damage (and is run by a short-line operator that occasionally engages in specious behavior that would make Vanderbilt proud, such as threatening to abandon the line in order to try and blackmail the state of Oregon into paying for repairs and upgrades).

One minor point of correction.

Whether the Coos Bay Branch is particularly vulnerable to floods is debateable — it doesn’t actually have a long history of distruptions, unlike the Tillamook branch — but the characterization of the operating company is correct only about its previous operator. For the last 2+ years it has been owned by the Internation Port of Coos Bay and operated by a contractor known as Coos Bay Rail Link, neither of whom have (to my knowledge) threatened to abandon. Quite the opposite in fact. The bad habits you describe, Scotty, were those of previous operator Central Oregon & Pacific, who not only don’t run the line any more (thankfully!) but have since been taken over by new owners.

We now return you to our regularly scheduled Portland-centric stories.

Good to hear, and thanks for the correction!

No question we have an export economy, but not the commodity manufacturing economy we once had (lumber and paper). Our manufactured exports are high value, custom products, i.e. computer chips or Western Star Trucks. High value manufacturing is more dependent on innovation than on transportation.

http://www.ubmfuturecities.com/author.asp?section_id=242&doc_id=526308

This Future Cities story was worth a link.

West Hayden Island is NO PLACE for an oval rail track facility, duh.

Why ship coal/oil/gas to temporary terminals leaving a mess

to be cleaned up later, maybe, maybe not.

We could export photovoltiac panels. We could and would

when a buck is only a piece of paper.

High-speed rail advocater, for certain include Corvallis on the Oregon HSR corridor, moderate expense. Also include the WES connection route at moderate expense. Could be a 5year plan once begun.

Great article. One thing that you only touch on tangentially is the ever-increasing size of container ships. The same economics you talk about are driving that as well. Even average sized container ships can’t get up the Columbia – and average sized ones were considered giant even ten years ago.

It’s a battle we can’t win.

Better to abandon the container market and continue to focus on our strength in break bulk shipping.

While break-bulk (handling of odd shaped cargos, like cranes or windmill parts, so on) is a strength for the port, the larger strength is in bulk commodities. If coal was a stable export commodity — and it isn’t, and likely never will be again — then it would (purely economically, not environmentally) make sense. Mineral export will continue to be a major player however, and it is likely that the lower Columbia River ports will remain one of the three largest grain export complexes in the world for many, many, many generations to come.