It is often said of traffic engineers that we’re an auto-centric bunch. I’m sure you’re aware of the list of sins—designing everything to minimize auto delay during the busiest 15 minutes and all that jazz. But what specific auto, pray tell, is at the centre of our auto-centrism?

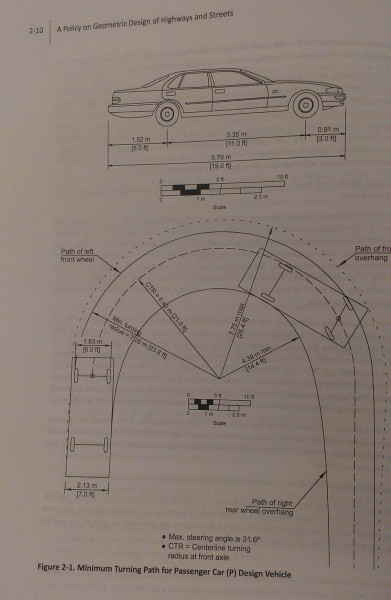

That would be what we in the biz call the “P Design Vehicle.” The “P” is a creation of the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. Though it doesn’t actually exist, it’s more important than most cars that do, as it is intended to be the standard passenger vehicle that roads and facilities are designed around. Want to build a drive-through access to your business? It has to accommodate the “P.” Want to include some on-site parking with your 40-unit apartment building (and if not, you’re out of luck!)? You’ve got to design it so the “P” can park. Building an adorable little Shared Court [pdf] to enhance the sense of community in your residential development? The “P” has to be able to comfortably navigate it.

Let’s go below the jump for a closer look.

Look closely at the sketch above, and then look at the dimensions. The fact that a vehicle with those particular properties is depicted as such a reasonable, innocuous looking thing makes that sketch one of the more egregious lies that you’re likely to encounter. At 19 feet in length, that little four door sedan is five inches longer than a 2014 Chevy Suburban or a 2014 Cadillac Escalade. The 7-foot width makes it three inches wider than a Hummer H2. Indeed, the “P” is more than an inch wider than the widest production car ever made, the 1954 Chrysler Crown Imperial. To be fair, there are a handful of cars, largely from the 1930’s, 40’s and ’50’s, that are longer than the “P,” but only the Hummer H1 and a handful of pickups are wider.

One might be curious about how the “P” has evolved over time. Below are the specifications for the initial model year of the “P,” taken from the first edition of AASHTO, published in 1965. All of the dimensions of the “P” are the same today as they were 48 years ago, except that the turning radius has shrunk by a little less than one percent. So hooray for power steering, I guess.

“The dimensions of a design vehicle should take into account trends in motor vehicle manufacture and be greater than those for nearly all vehicles which might be in use several years in the future…It seems appropriate, therefore, to use the dimensions of current models in choosing the dimensions of the design vehicle.”

– American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officals, 1965

7 responses to “Meet the “P Design Vehicle””

Good points on the size of the vehicle, but frankly I don’t worry about the passenger car in design as much as freight vehicles. The vehicles that make for turn radii that make the Dutch engineers laugh is a WB-67 that we use everywhere (as opposed to limited to freight routes). Isn’t that the challenge.

I agree completely, but if you were designing compact, urban development such as shared courts in the City of Portland, you’d worry about it. Designing modern, urban, desirable, safe neighborhoods while accommodating 50 year old engineering standards is an exercise in futility.

I’ve been to many foreign places where the streets simply can’t accommodate things like a dual-wheel F-size pickup, or a Hummer H2 (let alone an H1)–even your typical American minivan might have trouble.

Wow. So who do we talk to to get this changed?

This is a cart/horse problem. In Europe, they already had cities, roads, etc. They built their cars to fit them. Over here, we build our roads & cities to accommodate (rather large) cars. Seems odd to make the design of our environment serve the automobiles rather than making automobiles that fit our built environment.

PBOT has long had a paper cutout of a car, which started as a genuine side view of a Cadillac or some large car, to which they’ve added undercarriage obstructions. They would then draw up all proposed driveway profiles, and position this paper cutout to see if the car bottomed out on the driveway.

This may explain why new driveways are so shallow from the point of view of drivers. PBOT engineers also wanted to allow drivers to speed off the traffic lanes and across the driveway. They have told me this. They don’t want to design steep driveways that would force drivers to slow down (in the traffic lanes!) before crossing the driveway and sidewalk. They said drivers are afraid they’ll be rear-ended, so they want to move quickly out of the traffic lanes. Too bad for the pedestrians crossing the driveway, i guess.

I certainly don’t agree with the mentality of it, but the code is written for a 1959 Cadillac. I think I’ve seen 3 of these my whole life. Lawyers and judges write code these days, not engineers…