One of my big and untested (but unrebutted) hunches about the urbanism revolution, the drop in vehicle-miles traveled per person and so forth, is that it all flows from the rapid and mostly unexplained decline in crime rates that began in 1994.

As cities became safer, the first to notice were the young, poor, mobile and liberal. It seemed strange to our parents — but then, our parents’ bizarre fears of the central city seemed strange to us.

Just as, I’m sure, the rise of those fears (also known as the 1960s) seemed strange and unfair to my vaguely Germanic grandparents.

I’ve been watching the sixth season of Mad Men, the one that happens in 1968. Scenes on the main character’s once-quiet Manhattan balcony are being interrupted by screaming sirens; the middle-class couple who buy into the Upper West Side find themselves besieged by crooks. It was a rapid change in atmosphere that’s backed up by the statistics:

50 years later, local crime trends have reversed, perceptions of local crime have followed, and so have the tides of urbanism. As Mayor Hales put it in a speech last month, the flight to the suburbs was a round trip. The Don Drapers of the world are again buying Pearl District lofts, the Peggy Olsens are again renting two-bedrooms on Division or Thurman, and they’re both biking in to Wieden on Monday morning.

Was the crime decline that’s driving it all caused by pollution from leaded gasoline? Abortion rates? Data-driven policing? It’s not at all clear, though those seem to be the current favorites.

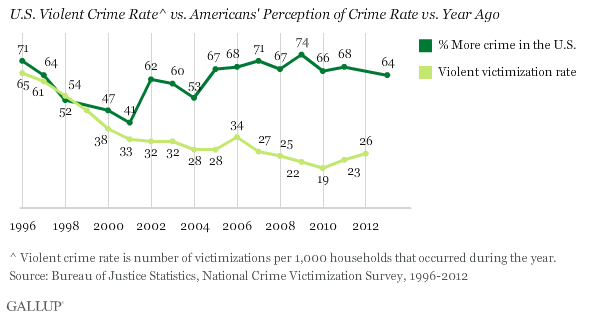

Whatever the cause, Americans do seem to be more or less aware that crime has gotten better, as long as you’re asking us about crime in our own personal lives. If you ask whether crime is a problem in the United States in general, most people, fed on Nancy Grace and Fox 12, will tell you it’s bad and getting worse. But when it comes to our own trains, parks and streets, we tend to be in closer touch with reality.

On the other hand — and if my hunch is wrong, I actually think this is why it is — there’s a chance the causality flows the other way. Maybe cities aren’t getting safer, and therefore more desirable and expensive, because urban crime has slowed. Maybe urban crime has slowed because poor criminals were, as early as 1994, being joined in the central city by gentrifiers and, ultimately, priced out of central cities — driven into neighborhoods where even a decent crook has to own a car to make a living.

Whatever the reason, I’ll be watching the various theories closely as they develop. Here’s why: what fortune giveth unto urbanism, fortune is just as likely to take away.

As someone who’s staked a lot on the continued desirability of living in the central parts of U.S. cities, I’m worried about the final two data points on this chart. And if I were you, you’d be worried too.

23 responses to “Did the great crime decline cause modern urbanism?”

“Freakonomics” has a good chapter that persuasively argues that the drop in the crime rate was related to Roe v. Wade. We keep good records on abortion, and the decline in crime started 15-20 years after Roe v. Wade.

Also, the longer prison sentences removed some career criminals from the community.

Interesting note: now that it is not lucrative to steal a TV or a stereo- certain types of breaking and entering are down.

High incarceration rates also reflect pot offenses (lame!) and as drug policies becomes less stupid we will see a decline in the states that legalize dope.

Anyway, I do think that perceptions of crime are an important thing to look at when you look at cities. And you are right, Michael, “perception” is the key word. The travelling gutter punks scare some people and business away from downtown Portland.

They create quite the “impression.”

I don’t buy the abortion explanation. To my knowledge, there was no widespread legal abortion in the past when crime rates were low, nor was there a sudden widespread ban on abortion imposed 15 to 20 years before the crime wave hit. I have the same problem with a lot of other hypothesis about the crime rate going down: does it also explain why crime soared in the first place? If not, why believe it?

As a lay person, I find the lead hypothesis most convincing, simply because it explains both the rise and fall of the crime rate. Put lead into the air? Crime goes up. Take the lead away? Crime goes down.

Have you read the Freakonomics analysis? It has always seemed sound to me, numbers-wise.

As a mom, I will tell you the family planning is important. I can’t imagine being a 16 year old mother- you would screw up big time. Postponing child bearing until the twenties would seem, to me, to lead to much better outcomes.

But if better family planning or fewer unwanted pregnancies was a factor in crime reduction, wouldn’t there have been a drop in the crime rate in the seventies and eighties, traceable to the introduction of The Pill in the early sixties?

It was the leaded gasoline. Near-perfect correlation with a ~20 year shift.

A few other contributors to the lower crime rate that have been hypothesized over the years.

* The digital economy–far fewer people carry large amounts of cash. The days that workers had to fear being mugged for their payroll are long gone.

* Video games–seriously. Some people who, in years past, would be out causing trouble in the streets, instead stay home with the XBox. The early 90s was when computing and videogame hardware powerful enough to be interesting, started becoming readily available. (I’m old enough to remember Castle Wolfenstein 3D and Doom, the first two offerings from Id Software, and being amazed…)

Engineer Scotty- I hadn’t heard the video game theory, but it has the ring of truth.

Didn’t some cities try midnight basketball games as a way to keep potential homicide victims of the streets? Certain crimes happen at night, with boredom as a contributing factor.

And don’t forget lead. Yep, the incidence of crime follows almost exactly the incidence of lead in the environment of toddlers. Twice in the Twentieth Century lead in the environment reached peaks: in the 1920’s with lead-based paints and the 1950’s with leaded gasoline. There are similarly two “crime peaks” twenty years later.

Elevated levels of lead in the blood of young brains has been shown to degrade the growth of the fore brain where self-control and delayed gratification arises.

No, lead is not the only reason people commit crimes. Some people just seem to be “born bad” in that they have genetically compromised higher brain functions. Of they suffer an injury to the fore brain and become uncontrollable. Or the fore brain is poisoned by other environmental or self-administered toxins.

And of course in hard times everyone is tempted to commit minor crimes in order to survive.

You can learn more about the lead-crime hypothesis at http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2013/01/lead-and-crime-linkfest

Oh, sorry, Michael. You already linked to the lead story on MJ. I’m reading on a dim screen and didn’t see the blue links until I changed the screen angle.

No sweat! That Drum piece is probably one of my top 10 transportation-related magazine articles ever.

I’m interested to know why illegal foreclosures that numbered in the hundreds of thousands aren’t included in this graph as violent crime.

I’d still put money on the boredom of the generation now driving the biking and urbanism waves being bored senseless in the suburbs and wanting some type of personal worth back in their lives. They wanted to be part of something versus the faceless, hidden and broken suburbs.

…I doubt it had to do with the crime decrease. Nobody has seemed to notice that the crime is in large part resettled in the suburbs, millions keep locating there. Oblivious to it…

Well, it hasn’t all resettled to the suburbs, as the first chart shows. More than two-thirds of the crime nationwide seems to have completely disappeared.

The recent uptick is because of the Great Recession. Once the economy comes back it will drop back down.

Do you see economic cycles anywhere else in the crimes per 1,000 trend? I don’t.

I haven’t looked, but I was under the impression that there was a well-established link between the health of the economy and the rates of some types of crime. I’m not a criminologist nor am I an economist, but I’m not going to let myself become frightened by a small trend.

Others have mentioned the phase out of tetraethyl lead in gasoline as a big factor in the reduction of crime rates and that makes sense to me.

Back to the original question, “did the great crime decline cause modern urbanism?”, I don’t know about anyone else, but I would not have wanted to live in one of the crime-filled cities of 30+ years ago, so there’s an n of 1.

Yeah, I’m not those things either. And I agree that it’s a small trend. I wouldn’t describe myself as frightened, just worried.

I too think lead looks like a very likely main factor.

Wait! All of these theories, yet no-one mentions the one theory that I have heard every time the drop in crime is mentioned: That the reduction in the number of people in the 18-30 age bracket (when most criminals are most active), is the primary reason crime is down. In fact, I have never heard any other theory mentioned. It’s almost settled social science!

The percentage of the population in that age bracket isn’t down by 70% since 1978, when the number of Baby Boomers in that age range was at its peak, let alone since 1996, which was a few years after the even the tail end of the Boomers had turned 30.

Doug,

Part of the theory that abortion lead to a drop in crime is the idea that women

who plan their families- perhaps waiting from 17 to 26 to have a child- raise healthier kids. The children of teenage moms face huge hurdles.

There’s been only one time I’ve thought about crime as a potential deal-changer while living in the city. That was during the Occupy protest, when it wasn’t clear how that was going to end. There was a moment when I looked at where the protest was and assessed the risk that a riot would spill over into the east side and potentially affect my family.

My perception of that risk may have been exaggerated, but that’s what it was. And it was enough to make me think, “if I lived in the suburbs this would not be an issue.”

I bring this up as a suggestion, that aggregate statistics may not be as relevant as black swan events such as the urban riots in the late 60’s. Maybe one reason people are coming back to the city is those events have become less prominent in living memory. A corollary would be that it’s pretty important to prevent such disturbances if we want to maintain the city as a desirable place.

Oof, I have to take issue with the notion of “preventing disturbances” such as protests, regardless of their issue and politics.

Free speech is more important than both property and order in our society.

That said, lead seems to be a pretty strong argument.

And whoever bought up population – currently the millenials are the largest generation in American history (bigger than baby boomers), so that doesn’t really hold up to the downward trend.

I’m not trying to run over free speech, I’m trying to run over riots and other instances of mass lawlessness that result in harm to city residents. Clearly laws can and do prohibit such activity, even if doing so might be construed as abridging free speech.

I think those events have an outsized psychological impact that is not linear to any objective measure of harm (such as number of properties vandalized or number of people injured). Is it coincidence that a few years after experiencing the most prominent urban riots Detroit was where the supreme court essentially approved white flight, explicitly acknowledging that was ok even if it resulted in de facto segregation?

I think riots are potential black swans, capable of fundamentally redefining people’s understanding of what it means to live in the city. I hope city leaders (whether elected officials or movement leaders) keep that risk in mind when contemplating mass action.