I had the opportunity to attend a “Travel Time Reliability” workshop at Metro a few weeks ago (I never said I wasn’t a wonk). The speaker was kind enough to forward the PowerPoint since I wanted to blog about a few of the slides.

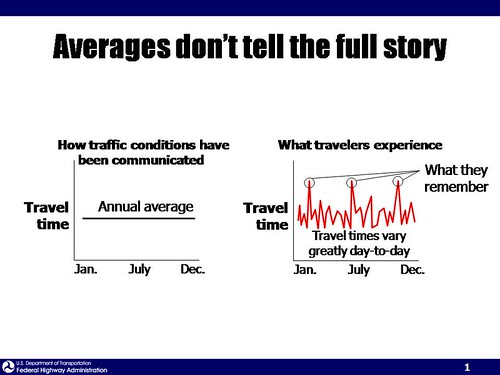

My point here is that when most people think about congestion, they think in terms of capacity constraints. But the reality is that the pain has to do more with unreliability. Not that the two aren’t related – more capacity does make you less sensitive to SOME of the factors that create reliability problems, but it’s an expensive answer and there may be more cost effective approaches (with way fewer negative environmental effects than adding capacity).

More after the break.

5 responses to “Congestion: Average Travel Time vs. Reliability”

Congestion pricing can do a lot to smooth the graph.

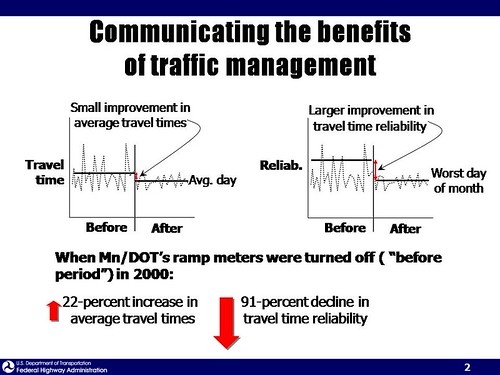

In this famous experience in Minnesota, ramp meters were turned off for a period (the ‘before’ segment in the slide). The result was longer after travel time AND less reliability.

The problem with the MNDOT study as it has been presented are twofold. It was quite clear that the lower travel times from ramp meters included a very large increase in travel times for people in the central city. The improvements for residents of distant suburbs offser those increases. This particularly important for the Portland region when you consider the impact of ramp meters on I5 southbound once a new Columbia Bridge is added.

The second part is that, while it did not ignore the short term equity issue, it did not address the long term impacts. It was brief experiment in which people did not have time to significantly alter their behavior or choices. So that distant suburb remained just as desirable a place to live. Where in the long run the increased delay likely would have lead to different people living in those distant suburbs and quite likely would have reduced the total traffic in the region. In short, it ignored the induced demand that shorter travel times over longer distances create.

The study also looked at the impacts on a limited part of the system – the parts managed by MNDOT. But the Twin Cities has a large number of robust local arterials paralleling most of their interstate system. Some of those are state highways, but most are just local streets. So reductions in travel times on those streets were not considered.

Finally, its important to realize that some of the MNDOT ramp meters had very long waits between vehicles. They were not being used to manage traffic on the freeway but to force users in the inner city to use local streets (or find a job closer to home) to allow quicker trips from the suburbs.

Important to remember this applies to public transit as well, not just private autos. How many times have we heard of MAX trains stuck in the tunnel, or delayed because something broke somewhere?

It was also part of the fate for the now-gone 95(X)-Tigard Express, which was chastised in an Oregonian article for being the ‘latest’ route [discussed here on Portland Transport]. That wasn’t the only route suffering from reliability problems. Try riding, with current schedule in hand, the 75-39th/Lombard or 72-Killingsworth/82nd during rush hour (or, find a coffee shop or something similar with a view of the street along those routes). Sometimes, with no rhyme or reason, no buses for quite a while, then two or three back-to-back – and usually not the operators’ fault, either.

And I think one of the problems is that Line 95 operated only during rush hours and bore the brunt of traffic problems. Even if other lines (like the 72 or the 75) have the same amount of unreliability during peak periods, it is somewhat hidden (averaged out) by evening and weekend trips that don’t have a problem staying on-time.

P.S. I found an Oregonian slide show about Line 95 here

nwjG Says:

Congestion pricing can do a lot to smooth the graph.

And those that can’t/don’t want to pay as the city grows denser? We destroy Portland for anyone who doesn’t live close to their job, even if their job is not in a reasonably priced/close in neighborhood?

Everyone who drives is not evil. I lived 26 miles from my job because I moved in under pressure, and signed a lease. I moved and still drive Mon-Fri because my office is about a mile from a bus line. It would take about 2 hours each way to commute, plus two miles of walking, to do what is a 15 minute drive.

I live in the city to avoid driving unneeded trips, and it’s quite effective. The problem is that I have a job I love in Vancouver, and I won’t move to Vancouver or leave a job I like going to.

Why do I live where I live, and work where I work? Predictable travel times, neighborhood, and reasonable economics. Even if things are hellish, I still am home in 35 minutes or less. Or, I could buy a $700,000 condo near my office, and live in an area I don’t want to.

Oh, and unlike Trimet, I can detour to a Fred Meyers or a Safeway if traffic is bad, and buy a trunkload of stuff. No planning, no “oops, this is an express bus.” Just pull off I-5 and take home a month’s worth of groceries.

There’s more than one reason most of us drive, sometimes.